Ethiopian Opal

NBA star Kevin Garnett, left, plays himself in "Uncut Gems," by Josh and Benny Safdie, along with Lakeith Stanfield, center, and Adam Sandler. They are looking at an Ethiopian opal in matrix that Sandler's character, Howard Ratner, is putting up for auction in the movie. Photo courtesy of A24 Films

The magical quality of Opals is the central metaphor of the 2019 movie “Uncut Gems,” starring Adam Sandler. A giant piece of Ethiopian opal, still in its matrix, is smuggled to New York.

“They say you can see the whole universe in opal, that’s how … old they are,” Sandler’s character, Howard Ratner, a jeweler and gem dealer on 47th Street in New York City, tells basketball star Keven Garnett when he shows the opal to him. Garnett is captivated to such an extent that he cannot play well without owning it.

Sandler’s character is enamored with the opal’s potentially huge sale price. He estimates that the piece weighs between 4,000 to 5,000 carats and, at up to his estimated value of $3,000 per carat, he sees millions coming his way. But the auction house he consigns it to values the piece at much less -- $150,000 to $225,000. Why?

“They say you can see the whole universe in opal, that’s how … old they are,” Sandler’s character, Howard Ratner, a jeweler and gem dealer on 47th Street in New York City, tells basketball star Keven Garnett when he shows the opal to him. Garnett is captivated to such an extent that he cannot play well without owning it.

Sandler’s character is enamored with the opal’s potentially huge sale price. He estimates that the piece weighs between 4,000 to 5,000 carats and, at up to his estimated value of $3,000 per carat, he sees millions coming his way. But the auction house he consigns it to values the piece at much less -- $150,000 to $225,000. Why?

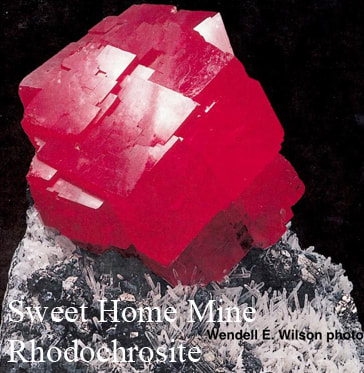

Ethiopian opal ‒ the featured gemstone in the movie “Uncut Gems” ‒ was first discovered in Ethiopia in 1994. Photo by Eric Welch/GIA

With opals, as with most gemstones, the final polished stones weigh only a fraction of their rough form. The specimen shown in the movie appears to have several opal nodules (though probably not black opal) inside the matrix of host rock, but that host rock appears to account for the majority of its volume. This means that it would be very difficult – in real life – to evaluate the opal and appraise its value until the matrix was removed.

“In real life, the opal nodules must be shaped and polished into gems after removing the valueless matrix, which often results in much more weight loss,” explained Nathan Renfro, GIA Graduate Gemologist® and manager of colored stone identification services at GIA. “Any realistic valuation of rough gem material is based on the potential for yielding polished gems and the risk involved in fashioning finished gemstones.”

Adding to that risk is the fact that, unlike most gems, opals are not stones or minerals.

Opals are formed from centuries upon centuries of seasonal rains that leach microscopic silica particles from sandstone, carrying them deep into underground fissures and cavities. As the deposited materials dry, the microscopic silica spheres become compressed into a closely-packed lattice. As light travels through this micro-structure, it creates a dazzling kaleidoscope of flashing rainbow colors, called play-of-color.

“In real life, the opal nodules must be shaped and polished into gems after removing the valueless matrix, which often results in much more weight loss,” explained Nathan Renfro, GIA Graduate Gemologist® and manager of colored stone identification services at GIA. “Any realistic valuation of rough gem material is based on the potential for yielding polished gems and the risk involved in fashioning finished gemstones.”

Adding to that risk is the fact that, unlike most gems, opals are not stones or minerals.

Opals are formed from centuries upon centuries of seasonal rains that leach microscopic silica particles from sandstone, carrying them deep into underground fissures and cavities. As the deposited materials dry, the microscopic silica spheres become compressed into a closely-packed lattice. As light travels through this micro-structure, it creates a dazzling kaleidoscope of flashing rainbow colors, called play-of-color.

The opal that beguiles the main characters in “Uncut Gems” was still in its matrix, similar to this piece of rough opal in matrix. Photo by Robert Weldon/GIA

The Many Colors and Types of Opal There are five major types of opals:

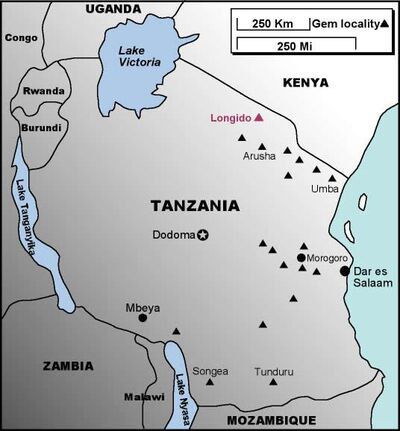

Ethiopia is the newest source, with the first discovery in 1994.

The most prolific source – which was named in the movie – was in found 2008 near a town called Wegal Tena in Wello Province. This material, mostly white opal, was formed from the silica from ancient volcanic ash. Another deposit, producing black opals about 30 miles to the Northwest of the Wello mine, was discovered in 2013 – a year after 2012, the year in which “Uncut Gems” takes place.

GIA has reported extensively on opals for many years.

Russell Shor January 22, 2020

Russell Shor is senior industry analyst at GIA in Carlsbad.

- White or light opal: Translucent to semi-translucent, with play of color against a white or light gray background color, called body-color. The opal specimen seen in “Uncut Gems” appears likely to be a representation of a white opal, despite its description as a black opal in the film.

- Black opal: Translucent to opaque, with play-of-color against a black or other dark background. They often sell for higher prices than white opals because the color contrast is much greater against the dark background.

- Boulder opal: Translucent to opaque, with play-of-color against a light to dark background. Fragments of the surrounding rock, called matrix, become part of the finished gem.

- Crystal or water opal: Transparent to semitransparent, with a clear background. This type shows exceptional play-of-color.

Ethiopia is the newest source, with the first discovery in 1994.

The most prolific source – which was named in the movie – was in found 2008 near a town called Wegal Tena in Wello Province. This material, mostly white opal, was formed from the silica from ancient volcanic ash. Another deposit, producing black opals about 30 miles to the Northwest of the Wello mine, was discovered in 2013 – a year after 2012, the year in which “Uncut Gems” takes place.

GIA has reported extensively on opals for many years.

Russell Shor January 22, 2020

Russell Shor is senior industry analyst at GIA in Carlsbad.

Few Common Questions

Ethiopian Opal vs Australian Opal?

Ethiopian opal is hydrophane which prevents crazing which in Australian is caused by drying out of the water content which creates hairline cracks. Ethiopian opal is more available and generally has a wider variety of color especially reds. Ethiopian Prices are lower and the sizes are much larger than Australian. Ethiopian opal is more durable resisting breakage better than all other opal including Australian.

Ethiopian Opal Price Per Carat?

The price per carat of Ethiopian opal ranges from $100 - $500 per carat based on the intensity, variety and patterns of color. Top quality gems will have color over the entire surface free of visible inclusions on the top surface of the opal.

What is Value of Ethiopian Opal? What helps value? How is supply effecting the value?

There is a large quantity of Ethiopian opal available which has kept the price low. Like most gems the top quality material is quite rare and commands a high price. The intensity of the color is what makes this opal valuable as the best Ethiopian opal have colors that are described as unreal looking like colored L.E.D. lights.

How to do you care for Ethiopian Opal? How is the stability?

Ethiopian opal once cut is highly stable. Being hydrophane it is absorbent and chemicals including hair products, dyes, oils and lotions should be avoided. Change in body color to more reddish orange in highly transparent slightly orange Ethiopian opal has been seen on rare occasion.

What is a honeycomb welo opal?

Honeycomb is a hexagonal pattern like the bees honeycomb. The reason it is valued is because the colors in the pattern are often incredibly intense.

Once in a decade, a new discovery of gems presents an opportunity to buy extremely high quality at very reasonable prices. This has been the case in the past with many gems, including peridot from Pakistan in 2001, bicolor tourmaline from Brazil in the early 1990s, sapphire from Madagascar in 1997 just to name a few.

When they are found, for a couple of years they are very inexpensive because of the quantity available. As with most finds, the quantity is finite and, as quickly as it is found, it disappears and the price inflates rapidly. This situation is compounded as we see more material on the market. The popularity increases because of this exposure to the public, and this demand also inflates prices.

Ethiopia vs Australia Today, we have one of those unique opportunities to buy extraordinary opal from Welo, Ethiopia, discovered in 2008. The quality is finer than any opal I have purchased from Australia, up until now considered to be the finest opal source. This Ethiopian opal is top crystal material, meaning it has high transparency, generally considered to be the finest quality opal. The transparency allows you to facet carve, or cab these Ethiopian opals.

The colors are evenly spread through the entire gem, and the intensity of the color is unreal as they seem to float in the gem and project from the surface. The number of colors in a single piece is only rarely seen in Australian material, and occasionally we even see violet, which is so unusual in opal from any source. The color patterns are highly varied.

The large sizes available also make this material unique. We have cut gems over 40 carats with the average stone well over five carats.

Being Hydrophane, much of the material is hydrophane, meaning it can soak up water. If placed in water, the material will become glass clear, and when removed, it will get milky, and after several days, the material will return to its original beauty. What this means is you shouldn't swim with it, while washing your hands will have little effect. The benefit of this material is that the riskiest part of traditional opal from other sources is drying out and cracking, called crazing, whereas this material will not craze from drying out.

One way to identify hydrophane opal is the characteristic of feeling sticky to the tongue or your finger. This characteristic also affects the weight, which can change with humidity.

The porous nature of Ethiopian opal has brought the charlatans out who are trying to change the colors of the opals through use of dyes and smoke treatments. We have seen violet colors from dying, and, although black opals occur naturally in Ethiopia, many are enhanced black color with smoke treatments. The color can and often is enhanced by enameling the back of the opal, which enhances the color of the Ethiopian opals that are highly transparent. This treatment is easily removed and has its benefits. This is an acceptable practice, assuming it is stated when sold.

Toughness is another characteristic of Ethiopian opal, which outperforms other locations. Tests by the Gemological Institute of America has shown that this opal is capable of withstanding drops to concrete from four feet without damage. All other sources failed this drop test.